Progress towards developing new pollination options for growers – Part 1 Bumble bees

David Pattemore, Heather McBrydie, Brian Cutting & Lisa Evans, The New Zealand Institute for Plant & Food Research Limited

Published Avoscene June 2017

For the last four years, our Pollination and Apiculture team at Plant & Food Research have been leading a research programme, “From Bee Minus to Bee Plus and Beyond”, to develop new pollination strategies for growers in New Zealand. Read more about this programme below.

[/restrict]

Our aim is to assist growers in reducing dependence on honey bees for pollination by providing a range of new pollination tools that can be used as needed. The research is supported by contributions from our partner orchardists and farmers, with funding provided by the Ministry for Business, Innovation & Employment, NZ Avocado, Zespri Group Ltd, Summerfruit NZ and the Foundation for Arable Research.

Our six-year research programme has three main objectives: developing techniques to use bumble bees in orchards; identifying ways to manage wild pollinators and increase their contribution; and improving the efficiency of honey bees as pollinators. Here we provide an update on our bumble bee objective; an update on the other two objectives will be included in the next edition of Avoscene.

Bumble bees are common across the country and are produced commercially to pollinate greenhouse tomatoes. Bumble bees can transfer large amounts of pollen between flowers and continue foraging in inclement conditions that might deter honey bees. Using bumble bees to complement honey bee pollination is likely to be a significant advantage for avocado production, especially as Hass flowers open at varying times during the day.

Wild bumble bees already contribute to pollination, but their contribution is currently unmanaged. Because bumble bee colonies are much smaller than honey bee colonies, the challenge is to provide sufficient colonies in orchard environments to make a significant contribution to fruit set.

Our bumble bee research covers two themes: developing an underground bumble bee ‘bunker’ to encourage the establishment of wild colonies (Figure 1), and developing techniques to reduce the cost of commercial production of colonies so that the cost of stocking orchards with bumble bees is comparable to that of honey bee hives.

The first theme aims to provide a very low cost, low management option that utilises the natural population of bumble bees already in orchards, whereas the second theme aims to give growers the option of bringing in a mixture of pollinators to pollinate their crop.

In spring, bumble bee queens seek a hole in the ground in which to establish their colony, so we are working on developing an artificial nest site based around a cement and pumice ‘bunker’ design that is buried in the ground. The bunkers have a lid to enable us to check for bees and a tunnel that leads from the base of the bunker to the surface for the bees to enter. The challenge is not only to get the queen bees into the bunker, but also to encourage them to establish a colony successfully.

We now have more than 1000 experimental bunkers installed in orchards and farms in Northland, Waikato, Bay of Plenty, Hawke’s Bay and Marlborough, including 10 avocado orchards. Over the last four years we have tested variations in bunker design, tunnel types, and nesting material, to determine the bees’ preferences. Overall, we found bumble bees in around 30% of bunkers, with successful colonies forming in about 18% of bunkers. We saw significant variation among orchards, with our most successful sites having colonies in 40-50% of bunkers.

Three big challenges that remain are: how to increase occupancy by queens of the most common species; how to increase the success rate of queens establishing colonies; and understanding the factors that drive the large variation in success between sites.

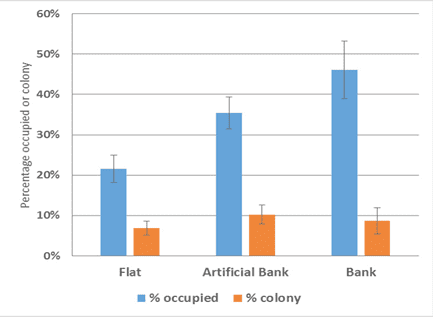

We have identified a few factors important in improving the success rate. Bunkers placed into banks were approximately twice as successful as bunkers in flat ground. In 2015 we created artificial ‘banks’ at the entrance of the tunnels (Figure 2), to test whether this would increase occupancy. In terms of the likelihood of finding bees in the bunkers, bunkers with artificial banks significantly outperformed bunks on flat ground, and were as successful as bunkers in existing banks (Figure 3). But this did not follow through to an increase in the rate of successful colony establishment, which remains a significant challenge.

In the last year we have been actively pursuing several lines of research. Firstly, we have continued to run experiments to understand what governs nest site selection by queens of the most common bumble bee species, which are less likely to occupy the bunkers than we would expect, given their prevalence. We’ve run choice experiments in flight cages (Figure 4), and tracked queen bees flying around a blueberry orchard as they were looking for nest sights using a world-first automatic tracking system (Figure 5).

Secondly, we are conducting grower surveys to determine what factors would make our bunkers an appealing option for growers. This information will provide us with direction for the future of the bunker research, to ensure we don’t pursue a system that won’t be practical in orchards.

Thirdly, we have been working to establish a method to estimate the total number of bumble bee colonies in orchards by looking at the genetic relatedness between bumble bee workers. This will help us to establish whether higher bunker success is due to higher background bumble bee populations or due to some factor at the site that makes the bunkers more attractive than natural nest sites. We aim to roll this method out on a larger scale in our orchards this coming spring.

Our second theme in the bumble bee research programme has been to develop a new model for commercial production of bumble bee colonies that reduces the cost per colony, and thus makes it affordable to place larger numbers of established colonies into orchards. Currently available commercial colonies are targeted at glasshouse tomato production, but are too costly per unit for large- scale orchard pollination. We are in the final stages of testing a new approach that would reduce the cost of commercially produced colonies using a different colony development method.

In the future we hope to see a range of techniques used to manage bumble bees for pollination. Growers might be attracting wild bumble bees into orchards using bunkers, and monitoring these nests, to have a firm grasp on the amount of pollination provided by these colonies.

Other growers might prefer to purchase commercial colonies to supplement wild colonies and achieve a higher pollination contribution by bumble bees. Used in conjunction with managed honey bees and strategies to encourage other pollinators, growers will be able to tailor their pollination management to the conditions of their individual orchards and the environment.

We will share more about our work with honey bees, flies and other pollinators in the next edition of Avoscene.

[/restrict]